As Right as Rain Dawit Samuel Habtamu’s journey from Ethiopia to China

At the edge of the sand dunes, beneath an endless blue sky in Inner Mongolia, Dawit Samuel Habtamu stood still. The wind there was sharp and cold, different from the dry gusts that sweep across the Ethiopian plateau where he was born. In this vast, unfamiliar landscape, Davu paused to hold onto the feeling. After winding through mountains and valleys, he had finally arrived. And somehow, this place felt like his own.

Keystone students' experiential learning trip in Inner Mongolia

Davu, as he is fondly called by friends, grew up in the Ethiopian capital city of Addis Ababa. His connection to Keystone Academy began in the eighth grade through distance learning classes, and by ninth grade, he had moved to China, joining a school community where he was part of a visible minority. The transition was complex, full of challenges and adjustments. But looking back now, Davu doesn’t separate the hardship from the beauty. Both have become part of his story.

On an experiential learning trip to Inner Mongolia in Grade 11, Davu picked up a weathered stone—its coarse surface holding traces of time. While his classmates moved ahead, he lingered, wanting to hold onto the moment. Today, that stone is still with him and presented it at the Character and Community Exhibition of Keystone’s Class of 2025 members. “This stone is like my future,” he said. “It reminds me not to forget where I come from. My past shapes everything that lies ahead.”

Now, as he weighs his university options—offers from the University of Notre Dame and Davidson College, and potentially, a joint program between Tsinghua University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong—Davu continues to carry that stone, not just in his hand, but in what it represents. It holds his quiet strength, his perseverance, and a deep sense of responsibility. “For the past five years,” he said, “I’ve lived as a minority in a Chinese community and become part of it. I’ve been shaped by Keystone, and I’ve shaped it in return. No matter where I go, I want to keep building bridges, to see others—and be ready, once again, to belong even as a minority.”

Building bridges

Before his younger brother was born, Davu’s closest companion was his cousin, just a few months older. They did everything together—attended school, played football, and got into the kind of mischief that defines childhood. In the yard outside their home in Addis Ababa, football transported them to a world of joy and possibility.

Ethiopia has only two seasons—rainy and dry. When the rains came, football came to a halt, and time seemed to slow down. But these rainy days gave Davu space to reflect. On rainy nights, he and his mother, Elizabeth Tesfaye, would stay up listening to the rain. Standing on the balcony, Davu would close his eyes and listen to the rain tapping against the metal roof, a soft drumbeat that seemed to lift him from the ground and carry him gently upward.

From left to right: Davu's cousin Nebiy, brother Amnen, Davu, and Davu's brother Nessi

Outside the rainy season, Davu and his cousin returned to their game. They both tried out for their school football team. His cousin was selected; Davu was not. In a country where football holds deep cultural meaning, this rejection felt sharp. Davu could sense the judgment from classmates, and the sting of being left behind by the cousin who had always been by his side. In frustration, he kicked the ball far across the yard and turned away.

But he didn't stay down for long. Davu resolved to improve—not just to make the team, but to prove something to himself. That summer, he began training on his own. He watched professional matches on repeat, broke down each player’s footwork, and practiced for hours each day in the yard. When a move didn’t feel right, he didn’t blame talent. “My connection with this movement isn’t strong enough yet,” he thought. So he tried again.

Whenever he felt discouraged, Davu remembered the sound of rain. It calmed him, grounded him, and reminded him of the strength he found in stillness. “If you live in a fixed mindset, you can’t challenge yourself,” he said. “Because you don’t believe you can grow. But it’s not that you can’t do what you’re not good at—you just need to look at it with a growth mindset.”

The next year, Davu made the school team. He came to Keystone in ninth grade and joined the football team in the following year. Then, he formed a deep friendship with Tony He, a teammate who would become both a close companion and a Chinese language mentor.

Still, adjusting to life at Keystone was not easy. The language, culture, and social customs were entirely unfamiliar. Although classes were in English, most students spoke Chinese outside of class. Davu couldn’t understand the conversations around him—the hallway chatter, the jokes between friends. “They can enter my world at any time,” he said, “but I couldn’t really enter theirs.”

Davu and his brother Nessi in Singapore

He felt like an outsider, lost in a place where even his own language, Amharic, no longer had a place. He missed his cousin, his family, the large dinners with injera bread, and the familiar sounds of home. He told his parents about the loneliness. His mother’s response was simple: don’t retreat—find a way forward. “If language is your obstacle, then learn Chinese well,” she told him.

Davu remembered everything it had taken to get here: waking at early mornings to attend online classes during the coronavirus pandemic, staying up night after night for a year before finally setting foot on campus. He had come nearly 10,000 kilometers from Ethiopia to Beijing. Retreat was not an option.

“I want to set an example for my younger brother,” he said. “He’ll face the same challenge one day, and I want him to see how it can be done.”

Determined, Davu dove into Chinese. He kept a notebook for unfamiliar words, asked questions constantly, and practiced speaking, even when it felt awkward. “Chinese is hard,” he admitted. “But I knew I had to push through.”

Teachers noticed his effort. In the Theory of Knowledge (ToK) class, he would look up every unfamiliar Chinese term, even asking about stroke order and handwriting. Kacy Song, Keystone Director of Libraries and Davu’s ToK teacher said, “He is learning anytime and anywhere,” and that “even words he didn’t need to know, he wrote them down, asked for the pinyin, and learned them seriously.”

The rain Davu once relied on for comfort became something internal. He no longer needed it to calm or guide him. His motivation now came from within—his quiet persistence, his belief in self-growth, his refusal to settle.

Davu attentively listening to classmates' opinions

When he entered the IB Diploma Programme, Davu chose the more difficult Chinese Language B instead the Chinese Language ab initio course, even knowing it might hurt his final grade. “I didn’t do it for the score,” he said. “I wanted to go deeper—to understand Chinese culture and connect with this place for real.”

In three years, Davu moved from Phase 1 to Phase 3, a process that typically takes around four years. At this stage, students, and even some foreigners who have learned the language for longer than Davu, do not typically choose Chinese B at that point. But Davu challenged himself to do so. By the final Diploma Programme (DP) class, he was speaking fluently, even using idioms. When his classmate Corban Whitney remarked that Davu’s Chinese had surpassed his own, Davu smiled but stayed focused.

For Davu, language isn’t just a skill. It’s a bridge—between cultures, between people, between who he was and who he is becoming. “Don’t wait passively,” he said. “If you want to truly connect with others, you have to start building the bridge from your side. The other person will build from theirs, and one day, you’ll meet in the middle.”

48 hours at the airport

"I don't like flying, because airplanes never seem to like me." Davu says it with a half-smile, but his experiences make it clear: air travel has rarely gone smoothly.

One of the most difficult moments came during the summer of Grade 10, when he traveled to Kyrgyzstan for a scientific research project alongside Science teacher Baldeep Sawhney and senior Arsh Noman. They transited through Kazakhstan—where Davu, unlike his companions, was stopped at customs.

"I was nervous. I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t know what," Davu recalls. Unlike Chinese passport holders, Ethiopian citizens need a special transit visa to pass through Kazakhstan. Davu didn’t have one. Customs gave him two options: fly back to China or wait for a direct flight to Kyrgyzstan without leaving the transit zone. Both options would delay him by two days..

He chose to wait. Though Mr. Sawhney and Arsh could have gone ahead, they stayed. “Davu is my student, and I want to stay with him,” Mr. Sawhney told the airport staff.

But waiting in an unfamiliar airport was far from easy. With no beds or rest areas, the trio attempted to nap on a series of chairs in the far corner of the airport. Right next to them, the massage chairs screamed reminders. Sleep-deprived and stranded, Davu felt exhausted, powerless, and overwhelmed.

It was during this sleepless stretch that he began reflecting on something deeper.

Amid this situation, the trio encouraged each other and discussed deeply on the issue of identity. As they successfully reached their destination and completed the summer research program, the experience crystallized a question Davu had long been asking himself: “What can I do to really help people in need?”

He thought of immigrants who may not be able to access basic services. “Without these resources, these people cannot live or work well,” he said.

During the DP, Davu chose the economics course—not just as a subject, but as a lens through which to answer that question. In Dorothy Mubweka’s class, Davu saw how economics could uncover hidden structures,

In his Extended Essay, he studied Colombia’s response to Venezuelan immigration. It was a dual concern: how to offer humane protections like healthcare while maintaining economic sustainability. “I realized economics isn’t just theory—it’s tied to real life,” he says. He hopes to study the field further in college to develop actionable solutions that support both immigrants and the countries that receive them.

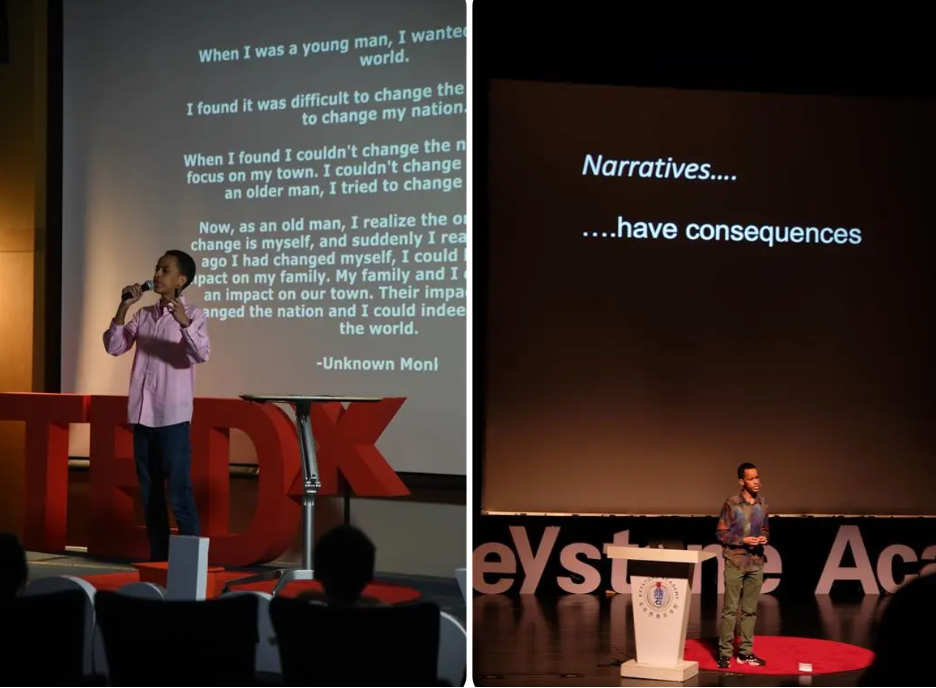

Davu speaking at two TED✖️Keystone events

Davu’s commitment to others runs through every part of his life. On the TEDxKeystoneAcademyBJ stage, he spoke on rediscovering kindness and escaping narrow definitions of love. His talks—filled with humor, clarity, and rhythm—are the most-watched TEDxKeystoneAcademyBJ speeches on YouTube. “Davu is born for the stage,” Richard Gao, a former leader of the Keystone Student Council, said. “But he never chased titles. He leads because he wants to serve.”

That spirit of quiet leadership is just as visible behind the scenes. Davu has been a member of Keystone’s Student Media Services (SMS) for three years, helping livestream events like Climate Change Conference (COP26), school plays, charity concerts, and graduation ceremonies. “Although we stand outside the spotlight, it is just as meaningful as standing on stage,” he says.

Davu as a cameraman

In September 2024, during a school-wide event on “How Service-Based Learning Influences the Future,” Davu served as a student volunteer, helping with everything from check-in to translation equipment. At the closing ceremony, he invited not just the speakers, but the behind-the-scenes staff—chefs, cleaners, translators—on stage for a group photo. “I wanted everyone’s silent contributions to be seen and cherished,” he says.

That photo, filled with laughter and shared pride, remains one of Davu’s favorites.

Percy Jiang, Keystone’s Director of College Counselling, said of Davu: “He never treated himself as a foreigner temporarily studying here. He treated Keystone as his home.”

That deep sense of belonging runs both ways. In the school cafeteria, younger children often gather around him. Even during the intense Grade 12 application season, Davu always made time to listen. “He gave the children time to share even their ‘insignificant’ words,” Mr. Jiang said.

In early 2024, Davu co-led a community initiative titled “Belonging” with classmate Tony He. Inspired by the words of his classmate Louis-Paul Rolland—“I won’t say I studied at Keystone. I’ll say I am a Keystonian”—they created posters inscribed with “We are all Keystonians” and collected handwritten New Year wishes from students and teachers. These posters became Spring Festival gifts for Keystone’s chefs, cleaning staff, and security personnel.

Davu and He Yuqi later delivered a speech on “Belonging” during a high school assembly. The words resonated so deeply that Executive Head of School Dr. Emily McCarren invited them to repeat it at the year-end faculty meeting. In the final moments, Davu asked the entire audience to stand and declare aloud: “I am a Keystonian!”

“It was a solemn and moving moment,” Tony He says. “That’s Davu—he brings people together with sincerity and purpose.”

Leave-takings

The sun streamed through the café window, warming the floor and dancing up the green wall. Sunlight lit the faces of Davu’s classmates, making the moment feel vivid and alive. Sitting among them, Davu wished he could freeze time.

It was the last ToK class. Teachers Kacy Song and Catherine de Levay had taken the class across the street to a café for their final session. Unlike usual classes filled with spirited debate, this one carried a quiet tenderness. Memories of past lessons—the intellectual clashes, the shared epiphanies—rose in everyone’s minds.

For Davu, ToK was one of the most meaningful courses. It wasn’t about fixed answers. It was about questioning the foundations of thought itself.

In class, students explored everything from the U.S. election to vegetarianism on campus, from identity and ethics to the definition of art and history. They examined the overlap between math and art, debated whether AI is inherently dangerous, and wrestled with big questions like: Does technological advancement guarantee progress in human understanding?

“In ToK, I felt that learning truly came alive,” Davu says. “If everyone agrees, the discussion dies. Real thought emerges in the deep waters beyond simple rules.”

That curiosity—pure and sincere—is what struck Ms. Song most. “Davu learns because he loves knowledge,” she says, adding that “He’s like Confucius in spirit.”

“No matter what field he will be engaged in in the future, Davu will be the teacher who can inspire others and bring positive influence to everyone.”

Davu’s contributions in class weren’t limited to offering ideas. He actively included quieter students in discussions. “He always encouraged others to speak up, especially those who were usually silent,” says Ms. Song. “His curiosity is sparked by difference.”

Davu describes ToK as a collaborative journey: “My classmates are artists, tech experts, historians. The real discoveries happened together—when we explored complexity and came back with thousand of ways of thinking.”

His notebooks are filled with classmates’ moments of brilliance. “The real challenge” he wrote, “lies not in your opponents. Rather it is with those who always agree with you.”

Davu’s approach to learning extended beyond the classroom. In Grade 10, he took over leadership of the Keystone Model United Nations (MUN) club. MUN’s format—role-playing as diplomats to tackle global challenges—deeply resonated with him.

“I loved trying to understand problems from other people’s perspectives,” he says. “When I attend conferences, I don’t take representing countries as an assignment. I truly embrace the nation and its culture.”

“My father Habtamu Ejigu is the one who taught me that MUN is about ‘making human connections,” Davu shared. Mr. Ejigu and Mr. George Nyamweya are Davu’s MUN supervisors.

Ding Shi MUN team participating in the 2024 Model United Nations conference at Georgetown University Qatar branch

He and his co-leaders guided younger students through rigorous MUN sessions, helping them prepare proposals and explore global issues with sincerity and depth.

This same spirit animated his literature and drama classes. English literature discussions lit sparks of insight; in Grade 9 and 10 drama, students co-created stories and performed them to explore emotional depth.

“When we’re truly collaborating, we forget the words but remember the feelings,” Davu says. “When it becomes so vivid, you reach the realm of reality that is hard to capture. It is a unique and profound experience."

“Maybe one day,” he adds, ““we leaders of tomorrow will sit down and talk like we do in ToK class. Maybe then we’d understand each other better.”

As high school came to a close, Davu found himself pausing in the halls, remembering the exact feeling of entering each classroom, of learning shoulder-to-shoulder with friends. He smiled to himself and whispered, “Thank you.”

Back in the café during that final ToK session, memories flickered through his mind like a film reel—those unrehearsed, irreplaceable moments of thought and dialogue. “Each class felt like walking through a cool, clear rain,” he says.

After saying goodbye to the rains of Ethiopia, Davu had found another kind of rain—one of thought and discovery. And in the café, he stood and said: “Thank you, everyone. We created this course together and felt the reality of learning. Let’s say goodbye—just like treating beautiful things that will eventually pass away.”

Davu still remembers something that Science teacher Portia Mhlongo said when he first arrived in Beijing. On the school bus from the airport to Keystone, his mother chatted with Ms. Mhlongo. One line stuck with him: “Many students think about what to take from school. But they should also ask what they want to leave behind.”

That is one of the principles that shaped his years at Keystone.”

“I think about Gao Jingbo, the student council president, quietly preparing assembly slides instead of eating lunch—never asking for credit,” Davu says. “Or Lisa Li, who gave a remarkable speech about body shaming and set up a free sanitary pad station in the girls’ bathroom. She started something, and now more students have joined her.”

He continues listing classmates—Henry Ye, Yolanda Wang —leaders who left legacies not through titles, but through quiet, persistent effort.

“To me, leadership means keeping your promises—especially when no one’s watching.