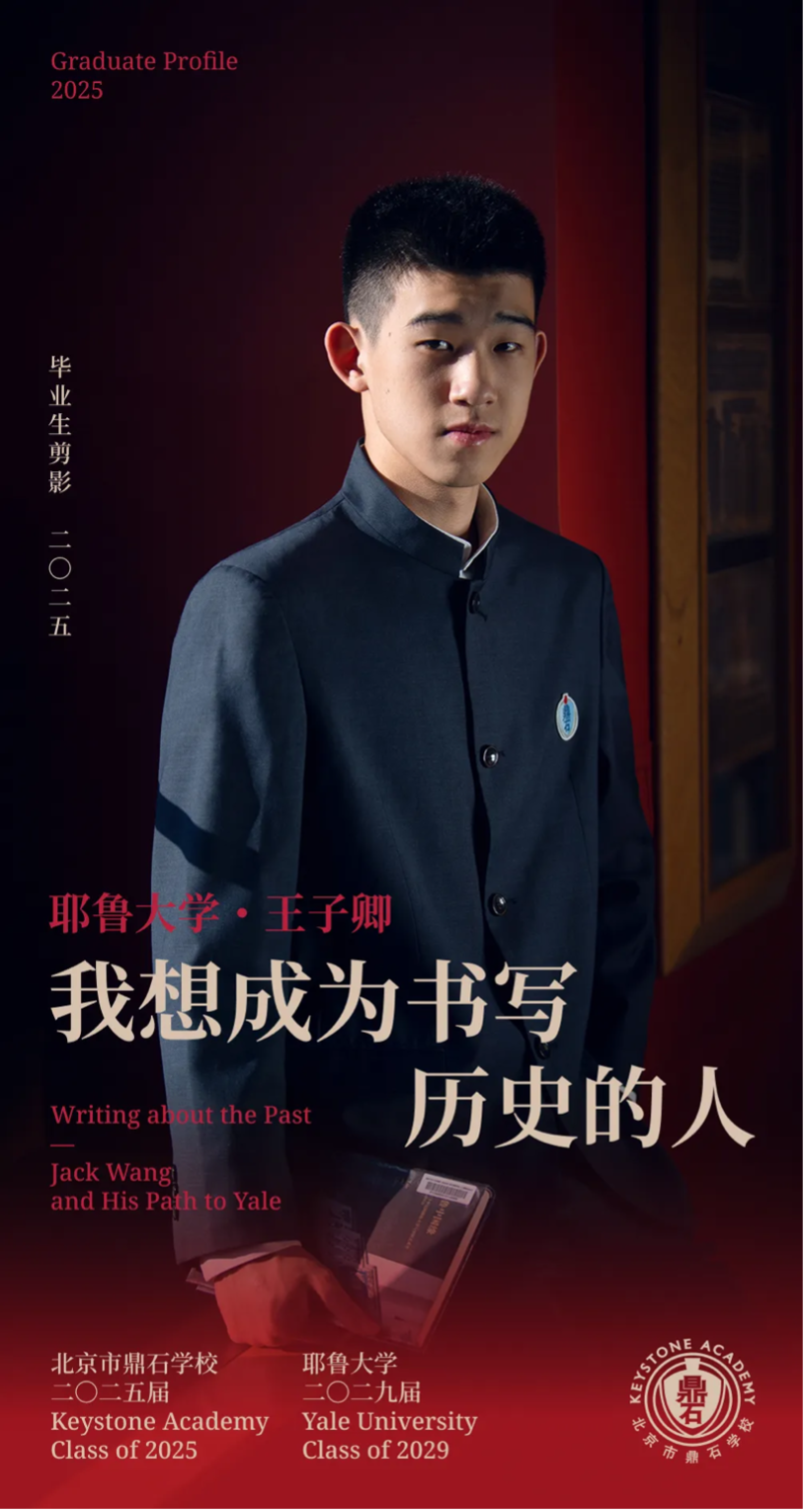

Writing about the Past, and Not Rewriting It Jack Wang and his path to Yale

The parents of Jack Wang once hoped he would follow in their footsteps and pursue a future in science. But in the fifth grade, he discovered his love for history. He looked up to historians and writers, especially Yuval Noah Harari, the author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, who inspired him to imagine a future where he, too, could explore humanity’s big questions through writing and research.

Over the years, Jack immersed himself in books on history, philosophy, and the humanities, reading the works of thinkers like Kant, Hegel, Laozi, and Jin Yuelin. His WeChat blog, with 254 articles published since 2017, reflects on both the past and the present. Aside from these, Jack has actively pursued historical research projects connecting him with his local community and beyond.

Step by step, he brought his vision to life.

“When you feel anxious, just do it,” he said. “It’s only when we really commit to something that we can begin to see our future clearly.”

In February 2024, Jack visited Yale University for the first time. Walking through the campus, he noticed the dates of major historical events engraved on the brick walls of Yale’s centuries-old structures. For Jack, Yale is both timeless and modern where he feels like standing at the crossroads of the past and the present.

Later that year, in December, he received his own place in Yale’s story: an admission letter. Along with the official email came a handwritten note from his admissions officer, a personal gesture that, to him, felt meaningful and sincere—almost like a small moment of history in itself.

Jack is the fourth Keystone Academy student to be admitted to Yale. He doesn’t see himself as someone who has “made history”, but rather as someone who wants to write not about his own but of humankind, from his humble perspective.

Jack’s Utopia

On January 25, 2025, the second day of the Spring Festival holiday, Jack updated his WeChat public account, Jack’s Utopia, with a new article titled “The Collapse of the Mediterranean Trade Network in the Late Bronze Age.” In it, he explored the reasons behind the mysterious end of a vast and prosperous trade system that connected the Mediterranean over three millennia ago.

Five days later, he followed it up with his 253rd article: “The Pursuit of the ‘Absolute Error’ Creed: An Unrealizable Fantasy.”

In the seven years since founding Jack’s Utopia, Jack has published more than 260 articles—averaging nearly one a week. Maintaining that pace would be challenging for any professional journalist, let alone a student balancing academic pressure. But Jack has a deep impulse to write. Through Jack’s Utopia, he transports himself across different times and places, reflecting on history, current events, art, philosophy, and more, in both Chinese and English. Each article raises new questions and offers his evolving answers. Writing, for him, is a way to sort through his understanding of the world—and to test the limits of where words can take him.

Jack launched Jack’s Utopia in 2017, just four months after arriving at Keystone. At first, he wrote simple historical stories. Then came his reflections on different eras. Over time, his work grew into deeper analyses of historical events and commentary on current affairs.

What started as a personal project slowly became something bigger: a platform for his ideal of understanding the present through the lens of history and, through that understanding, working to reduce prejudice and division in the world.

Jack’s love of history started in fifth grade, when a single history class sparked his curiosity about the past. Since then, he has tried to view history as something alive—a way to connect the past with the present, and himself with his own era.

He’s drawn in by the narrative of historical periods, and the rich stories coming from the people, places, and ideas that shaped those eras. His articles take readers from the Hittite civilization to the Qin Empire, from the violence of the Viking Age to the beauty of ancient Greek temples. He writes not only to retell these stories, but to explore the forces that drive historical change.

Reflecting on the Viking Age, for instance, Jack once wrote:

“Undoubtedly, the Vikings’ violence and bloodthirst caused a catastrophe for the Europeans. But looking at history from an overarching perspective, were all destruction extremely detrimental to the light of civilization? I think not. I believe the Vikings contributed positively to the unification of multiple nations in Europe, brought deep-rooted changes to the European political systems, led to the birth of mercantilism or the outlook of global trade, and created cultural merging through their bloody conquests. These contributions did not fade away together with the Viking Age. Instead, most became the cornerstones for Europe and the Western world at large we see today.”

Seeing his passion for history, Jack’s parents became his strongest supporters. When he reads history books, his mother often goes along with him. He makes mind maps in English; she takes notes in Chinese. Then they discuss and debate, sometimes at home, sometimes on the car rides back to school. His parents regularly challenge his ideas, pushing him to consider new perspectives and ask sharper questions.

One of Jack’s favorite memories is standing beside his mother in the kitchen at noon, talking loudly over the clatter of pots and pans about Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. They could barely hear each other, so he had to shout just to keep the conversation going.

Those same conversations continue with his admissions counselor, Sonja Song, who shares his love of history and often becomes a thoughtful listener to his latest ideas. Keystone Dean of Admission Chris McColl and Dr. McCarren have also become regular readers of Jack’s Utopia, joining him in discussions about patterns of the past and possibilities for the future.

Moments like this remind him history isn’t just an academic subject but a connection that carries warmth, emotion, and meaning.

“History is also about the future,” Jack said.

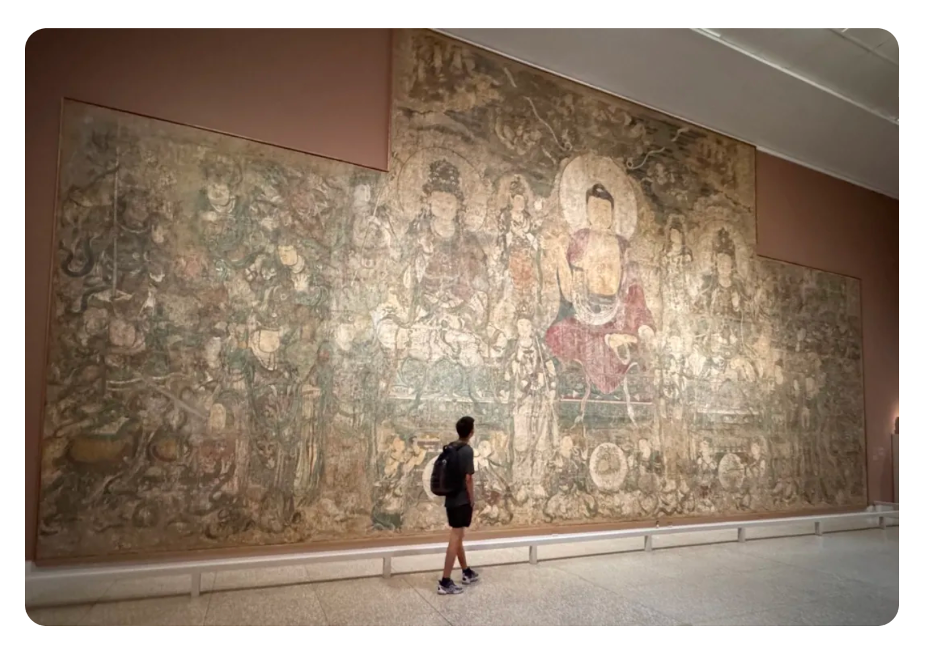

He has spent hours standing before ancient ruins, reflecting on what they tell about human civilization. He has thought deeply and quietly at museum exhibits on war and peace, rise and collapse, division and reunification. He has searched for patterns in the works of Socrates, Nietzsche, Kant, and Hegel—trying to answer his questions with philosophy, and to find the future inside the past.

For Jack, history is endless. “Without the memories of the past,” he said, “how could we have today? And without what we do today, how could there be a future?”

Even as the world changes at incredible speed—where technology advances and globalization deepens—conflict, discrimination, and cultural divides persist. Wars continue. Trade barriers rise. And yet, Jack believes people across regions, nations, and even centuries have more in common than we sometimes realize.

Jack and his university advisor, Teacher Sonja Song

Through dozens of articles in Jack’s Utopia, he has explored these connections. He’s written about the shared symbols, beliefs, music, art, and ideas of the East and the West. He looks to history for ways to better understand the present and the future. And while he knows conflict is inevitable, he hopes that by changing how we see each other—and by approaching differences with empathy and fairness—people of different nationalities, religions, and ideologies can find more respect, cooperation, and dialogue.

This belief is the thread running through Jack’s Utopia. It’s the ideal Jack is still pursuing through his writing.

When asked what learning means to him, Jack answered simply: he wants to use his knowledge—and his sense of justice—to make the world a better place.

In one of his articles, posted in Jack’s Utopia, Jack wrote:

“Human history brims with destructive impulses, an endless cycle of brutality and annihilation that ignites wars, genocide, and the downfall of civilizations. Yet, inscribed within our very nature exists an opposite quality. This inherent aspect has guided humanity to establish a spiritual civilization that reaches beyond basic necessities—a world abundant with imagination, compassion, art, and philosophical contemplation. Within this fundamental duality of human existence, we must continuously nurture hope for what lies ahead.”

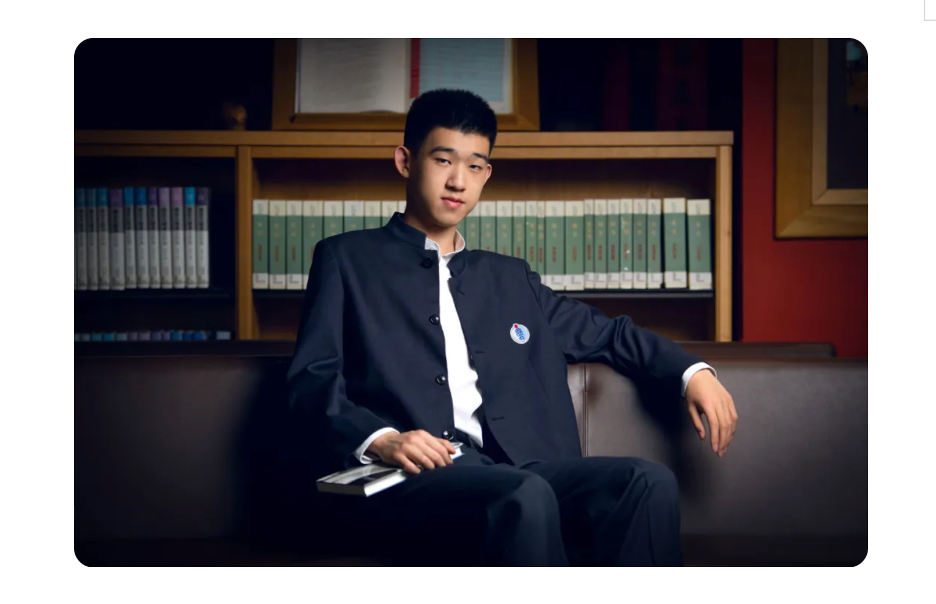

In Jack’s Utopia, audiences can see the ideals of a young scholar at work—his hunger for knowledge, his belief in fairness, and his desire to take on responsibility.

After over seven years and 254 articles, Jack has turned his love of history into real work and lasting action. With each essay, he lays another brick in the foundation of his vision—a bridge connecting people across countries and cultures, and a shared “utopia” built not just for himself, but for others, too.

Links in reality

One evening in Kenya, Jack dimmed the lights of a small house on the grasslands as his Bangladeshi roommate laid out a blanket to pray. Though Jack had studied Islam in textbooks and explored its history, watching this quiet, personal ritual moved him deeply. In that moment, cultural differences felt real and powerful—not as an abstract idea but as a lived experience.

“It’s hard to describe the shock of this cultural difference in words,” he reflected. “You can only feel it when you’re there.”

In 2023, Jack traveled to Kenya with Keystone students and Director of Experiential Learning Chris Cartwright and Executive Head of School Dr. Emily McCarren to attend the Round Square International Conference. There, he and his roommate—two people from different backgrounds, beliefs, and traditions—began talking. Their conversations weren’t about the broad strokes of religion or politics but small, everyday details: family traditions, prayer habits, childhood memories. Jack realized that real understanding often starts not with differences but with shared, ordinary experiences.

Reflecting on this, Jack launched an interview project during the conference. With another student, he spoke with attendees from around the world, asking simple, human questions: “How do you view childhood?” “How do you think about death?” “What are the customs around daily life in your culture?”

The responses revealed just how naturally people connect when they begin with empathy and curiosity. Trust, he found, grows out of small exchanges, and real dialogue follows.

Jack brought this project back to Keystone, recruiting students to interview teachers and classmates from countries like Uganda, Greece, Ethiopia, and India. In more than 20 video interviews, they captured honest reflections on life, traditions, and identity. These conversations confirmed what Jack experienced in Kenya: the similarities between people are far greater than the differences.

This belief continues to guide his work. After graduation from Keystone, Jack hopes to build new cultural bridges at Yale, sharing Chinese culture and learning from others. He also hopes his classmates from Keystone will carry this spirit into their communities, becoming ambassadors of cultural exchange wherever they go.

Jack’s commitment to connection has shaped much of his work at Keystone. After three years in Keystone’s Round Square Council, Jack, who was then a high school junior, became its chair and helped grow its membership from 30 to over 100 students. During the pandemic, he worked with international schools in Ningbo and Shenzhen to develop a Chinese language lab, offering online courses on Chinese language and culture to over 170 students from more than 30 countries. Inspired by this success, Round Square expanded the concept to include labs in French, Japanese, and even New Zealand Māori, turning language learning into meaningful cultural exchange.

“As an organizer of the Chinese language lab,” Jack said, “I felt how it allowed students to share cultural values in a way no ordinary course could. There were no barriers, just direct, equal communication between students.”

This same vision of connection shaped Jack’s Utopia and guided his KAP (Keystone Activities Program) on linking Eastern and Western civilizations. Through history discussions with 15 students from Grade 6 to Grade 9, he encouraged them to explore both their national identity and the shared humanity across cultures.

Even in small moments, like reading with primary students in the Keystone Library through the “Reading Buddies” KAP, Jack found meaning in bringing people together. High schoolers and young children, two groups who might otherwise never interact, shared stories and time, giving each other unexpected warmth and companionship.

For Jack, whether through history, dialogue, or daily life, every connection strengthens the links that hold our shared world together.

Everything is connected, like history

At the personal design project exhibition, Jack showcases his exploration results in "Jack's Utopia" to the community.

While his parents encouraged him to focus on math when he was in Grades 6 and 7, Jack’s heart belonged to history. Ancient civilizations, Viking sagas, Sumerian texts—these stories captivated him far more than equations. Still, when choosing Diploma Programme (DP) courses, he wanted to challenge himself. He enrolled in the most rigorous math option: Analysis and Approaches.

At first, it was overwhelming. Complex calculus and advanced functions pushed him far beyond his comfort zone. Most students interested in the humanities avoided the class entirely. After a difficult start and disappointing test scores, Jack worked closely with his math teacher, Amanda Shen, and his parents to adjust his study strategies. With renewed confidence, he persisted, eventually earning a perfect score of 7.

This experience changed the way he thought about learning. Rather than separating math and history, Jack began to see how they could support each other. He applied mathematical modeling techniques to a historical research project called “Stolen Relations”, led by Brown University Professor Linford Fisher. The project focuses on the enslavement of Indigenous people in early American history.

While searching through fragile 17th-century court records and handwritten diaries in Rhode Island, Jack felt the thrill of uncovering the past firsthand. His years of writing, research, and analysis came together in a 10,000-word paper that earned high praise from Professor Fisher, who commended his creativity, rigor, and academic resilience. Jack’s mathematical model, designed to find patterns in historical data, further impressed the team and revealed the vast potential of interdisciplinary research.

This work opened a new path forward. Jack hopes to combine history with mathematics or computer science in college, believing history has never existed in isolation. For him, it has always intertwined with literature, science, philosophy, and music—fields that deepen his understanding of the past and present.

That same curiosity drives Jack’s Utopia, his WeChat blog. In one series, “History and Classical Music,” he uncovered the historical moments behind the works of Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, and others.

Music, like history, has become an emotional anchor in his life. After 13 years of piano, Jack still finds himself moved to tears by pieces like Chopin’s Ballade No.1 in G minor, Op. 23, hearing the echoes of heroism, longing, and resilience from centuries past. Though his teacher once encouraged him to approach the piano objectively, Jack has always felt the weight of history in every note. In these moments, time and place dissolve, and the shared emotions of humanity come alive.

That sense of connection extends beyond the page and the keyboard. Jack believes history is not only something we study—it’s something we create. At Keystone, he’s seen this firsthand. In the history KAP club, Linking the East and the West, his passion inspired younger students like Raymond Zhang to launch their projects, exploring topics like global legal systems and ancient languages.

Through all these moments, Jack is reminded how much the people around him have shaped his story. He often thinks back to his first week at Keystone, in fifth grade, when a classmate, Oscar Zhou, reached out with a simple question: “Can we be friends?” That invitation sparked a friendship that has lasted seven years and counting.

It’s the same with his roommate Tony Xie, whose optimism has grounded Jack through challenges. When Jack faced failure, Tony helped him see it not as a monster but as a natural part of life. And when Tony needed someone to listen, Jack was there. For four years, they’ve continued to choose each other as roommates, creating a steady partnership built on mutual support.

Jack has come to realize that these connections are what make history matter. They exist between people, across cultures, through time and space—linking the East and the West, the past and the present, the known and the yet-to-be-discovered.

One night, just before summer break, Jack shared a National Geographic photograph of the night sky with his friend Andy Ren. Stars filled the frame—bright, endless, mysterious. Andy was mesmerized. Over the summer, he borrowed the magazine from the library and convinced his mom to take him out to see the stars for himself.

Months later, back on campus, Andy found Jack and shared what he had discovered:

“When I saw the starry sky in National Geographic, I thought it was just Photoshop. But when I saw it with my own eyes, I knew—that’s the real starry sky.”

For Jack, that’s exactly what history is. It’s not just something you read about. It’s real, vast, and full of light—waiting to be seen and connect us all.

Most of the records in Jack’s collection contain classical music. Ancient melodies and historic sounds are preserved in the delicate, sinuous grooves of the vinyl, bringing a fresh, life-affirming quality to each playback—like an artistic parallel to life itself.

People often call utopia an unreachable destination, an aspiration difficult to fulfill. Yet over these past seven years, Jack has, through devoted action and genuine passion, with spontaneous, pure, youthful dreams, maintained a sense of pain, vigilance, questioning, and skepticism within himself. He looks toward distant horizons and moves steadily toward that ideal place.

As Professor Luo Xin of Peking University writes in a book: “The future may not be exactly what we expect it to be, but without those expectations and efforts we invest, this future would become something else—something we would find even more unacceptable.”

History takes shape through storytelling, and our lives are constructed through our words and actions.

Jack chooses to build a utopia that belongs to the future.